One of the great pleasures of studying local history is that a single person or event can lead you on to another person or event and then to another and, suddenly, you have links in a chain that takes you far away from your original starting place, writes DR ROBIN LEE of the Hermanus History Society. The chain links can take you deeper into or further back in time in your own community, or they can take you far away from where you started, into a world you never dreamed had connections to you

This topic takes the second course away from our small community in Hermanus to Johannesburg, England and Germany, and from today to the early and mid-20th century. It is the story of Roger Bushell, whose name appears on the War Memorial above the Old Harbour with other residents of Hermanus who died in the Second World War. Roger Bushell was born in the town of Springs, in what is now Gauteng, in 1910. His father was a mine manager who had become wealthy and he sent Roger to a private preparatory school in Johannesburg in 1917. This was Park

Town School, opened by Lord Milner in 1902 in a tin shanty in Girton Road, Parktown, then the swankiest suburb in Johannesburg.

A few years later it moved to Mountain View to occupy luxurious premises in a house built by super-rich Randlord, Percival Tracey, who had died in 1907 and left the building for this purpose.

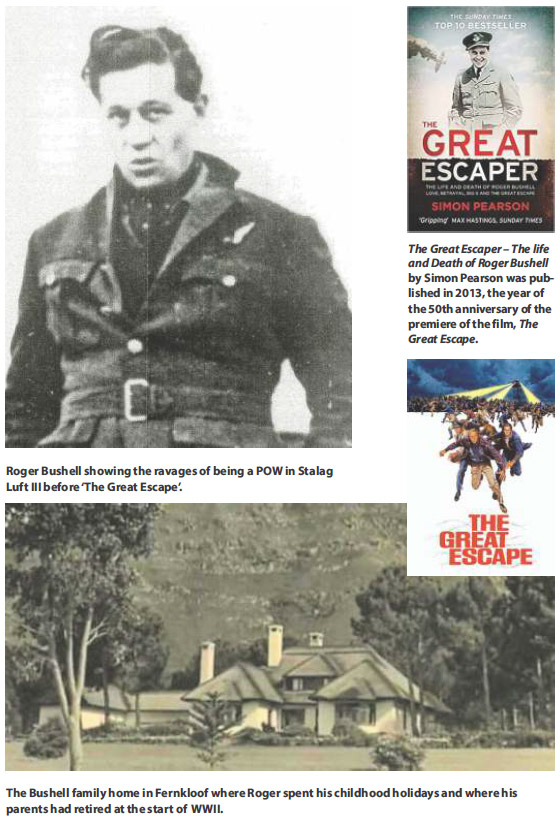

The house still stands today, with its white pillars clearly to be seen against the green hill. It has been restored as corporate offices. Roger’s grandparents lived in Hermanus during his prep school years and he spent his holidays with them every year in the summer. They owned a house in Contour Street, Fernkloof, which still stands today. There is a photograph of Roger, aged about 13, with a surfboard, that could only have been taken in Hermanus.

After prep school Roger was sent to Wellington College in England and then studied law at Pembroke College, Cambridge University. For a few short years he practised successfully as a barrister in

London, but when World War II broke out he immediately joined the Royal Air Force, assigned to 92 Squadron, flying Spitfires. His fighting experience was quite short. In 1940 he was attacked over Calais by two Messerschmitt 110s and his aircraft was badly damaged. He managed to land it in enemy territory. At about this time Roger’s parents moved to Hermanus and were living in the family home in Fernkloof. Letters he wrote to them went to the post office in Tenth Street, Voëlklip. He wrote to them about his capture:

The old girl burst into flames. And as you can imagine I got out as quickly as I could. I thought I was well behind our lines but to my rage and astonishment a German motorcyclist came round the

corner and I was taken prisoner. It was the duty of every Allied officer to try to escape and Roger Bushell took this duty very seriously. Almost immediately he escaped from a low security prisoner of-war camp (Dulag Luft), but was recaptured. He then escaped from the train taking him to a more secure camp (Stalag Luft I) and reached Prague, where he was hidden for 8 months by a Czech family. He had a relationship with a daughter in the family, but, after it ended, she told her new boyfriend about Bushell. The boyfriend betrayed Bushell to the Gestapo for a reward. Bushell was recaptured and the entire Czech family shot.

Roger was sent to the highest security prison (Stalag Luft III), after vicious interrogation and torture by the Gestapo. He immediately began planning for a large escape, and created an

“escape committee”, with himself as chairman, known as Big X. Under his leadership 600 RAF officers became involved in what history calls “the great escape”.

Details of the great escape are well known, from a book published in 1953 by Paul Brickhill and a film released in 1963, with Sir Richard Attenborough playing the role of Roger Bushell. In brief, the prisoners dug three escape tunnels (Tom, Dick and Harry), so that if one or even two were discovered, work could go on in the third. Two hundred men were equipped with realistic German civilian and military clothes, forged papers and money (all manufactured by prisoners from materials available in the camp), and on the night of 24 March 1944 the escape began.

Unfortunately, only 76 men managed to crawl down the tunnel and get into the woods surrounding the camp before the German guards were alerted and further escapes prevented.

Nevertheless, 76 was a huge number to escape at once and the escape was a big boost for Allied confidence and propaganda. Hitler was enraged and ordered the summary execution of every one of the 76 escapees captured. After some days 73 were recaptured and 29 of these were shot in the back of the head by Gestapo members. Roger Bushell was one of those executed.

The Gestapo official who shot Bushell, Emil Schulz, was tried for murder at Nuremberg in 1946, found guilty and sentenced to death. The memory of Roger Bushell lives on in Hermanus. His name is among those on the War Memorial near the Old Harbour and is the only name of someone never to have lived here permanently, though his parents were living here at the time of his death. His parents also made a presentation to the Hermanus High School, in remembrance of their son who (incidentally) could speak nine languages. The two coveted Roger Bushell prizes for character are still awarded annually at the prize-giving of the school and his name and the story of his great courage live on.

Amazing, where the links in a Hermanus history chain will take you!