The opening of the New Harbour was one of the factors that led to the ‘perlemoen boom’ that lasted about 20 years. Between 1950 and 1970, Hermanus saw a development that brought a variety of different people into the town and kept the New Harbour busy for the duration. But it also pointed the way to several developments in the 21st century, writes ROBIN LEE of the Hermanus History Society.

At about the same time that the New Harbourcame into operation in 1952, over-fishing by boats and trawlers from outside our area drastically reduced the catches of fish. The trawlers removed hundreds of tons of silver fish (called ‘doppies’ by the fishermen) which were the food source for larger fish which obviously then left the area.

In the 1950s and 1960s an alternative catch was found – perlemoen or abalone, as the rest of the world knows it. Perlemoen had long been part of the local diet and, though there are no records to prove this, a small quantity may have been transported inland and sold to farmers.

However, all that changed when Brian McFarlane Snr devised a method of cooking and canning the flesh and found markets in the Far East, especially Hong Kong. He opened the first abalone processing factory in 1956 and bought most of the harvest for export.

During this period several million individual perlemoen were harvested ‘by hand’, with the New Harbour used as the base for the numerous boats that carried divers to the kelp beds where the perlemoen were to be found. Suddenly a subsistence or leisure activity in Hermanus became big business and the news spread, attracting young men from all corners of the world. Many of them had been divers in the Royal Navy during World War II and made their way to Hermanus, seeking to make quick money.

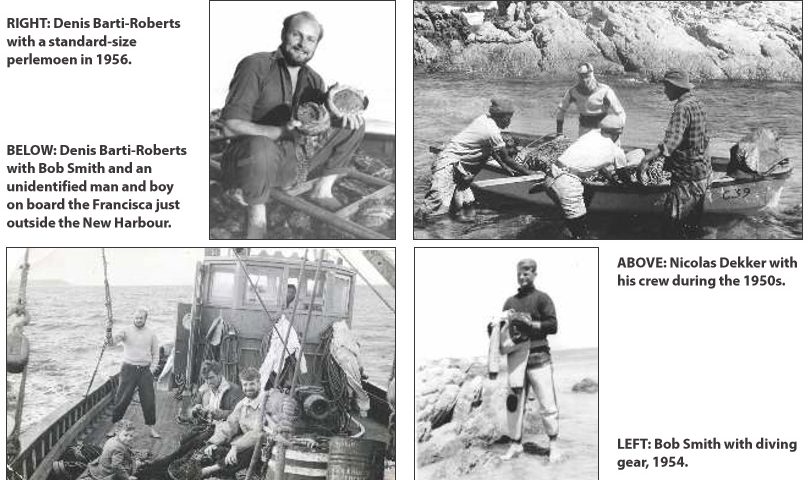

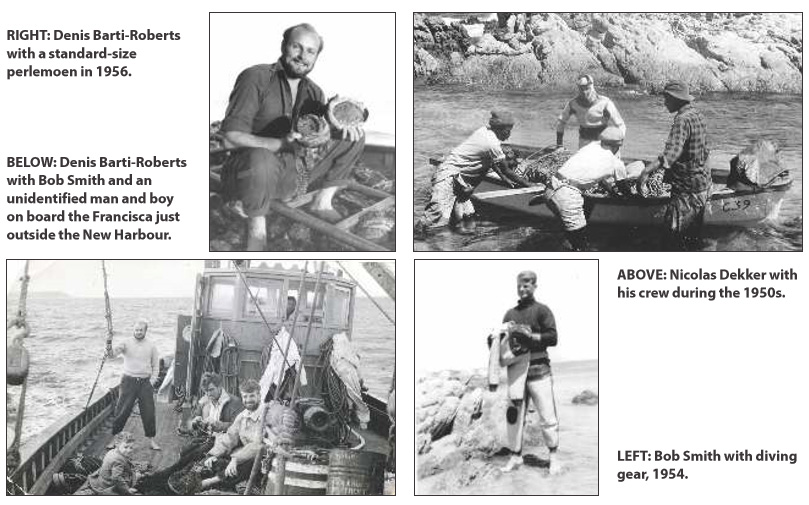

Gertrude Grant, a longstanding resident of Hermanus whose husband, Alexander (Sandy) Grant established the first pharmacy in the town (still trading as Alex. Grant Pharmacy), knew many of the divers by name – Jacob and Martin Nielsen (Denmark); Nicolas Dekker (Netherlands); Stan McCrae; Arthur Major; Denis Barti-Roberts; Bob Smith; Dev Tucker; John Carstens; John Mead (all UK); Jim Christie-Smith; Peter, Billy and Reggie Dodds; Charl (Bokka) du Plessis; Matt Hale; Roy McGregor; Gerrie Lotter; Denis Pretorius; Koos Wilkinson; Murchen Arendse; Dave Elliot; Peter Mason.

Several of the divers left accounts of their lives here; others are still living in the area and I was able to interview them. We can reconstruct their lives quite accurately. At first, these young adventurers ‘skin-dived’ – that is, they had no breathing equipment, not even a snorkel. Nicolas Dekker describes how they did it:

We had no diving suits, in 1952 these things were unknown in South Africa and the water temperature was 12 centigrade… To harvest the perlemoen we had blown up car tubes to which were fixed circular nets that could hold about 80 shellfish. The perlemoen grow on the rocky bottom between the kelp stalks from six to twelve metres deep. You take a few deep breaths, put your head down and your legs up and down you go. Then with a big screwdriver you lever off a perlemoen and swim up to put it in the net that you’ve tied to a kelp stalk.

The water felt very cold. None of us were fat blokes and none of us could stay out longer than an hour. We swam back to shore leaning on our tubes to get our torsos out of the water and into the sun. When we came out we lit our already prepared fire and stood around it to warm up… and a quarter of an hour later we had recuperated enough energy to go and count our perlemoen.

This practice was considered dangerous and was stopped in 1954. For a while divers used conventional snorkels but then a local diving outfit was developed and ‘skin’ diving was replaced by compressed air – but the equipment was almost hilarious if it had not been so dangerous. This is Gertrude Grant’s description of a set up that was supposed to keep an adult male working at a depth of 6 – 8 metres:

Since the men started using foam rubber suits and breathing tubes supplied with air from a compressor on the boat, they can stay down for four or five hours. The breathing apparatus is, to say the least, primitive. The diver wears a mask, and a nose clip and holds a mouthpiece between his teeth. His air is supplied to him through an ordinary plastic hose pipe from a garage air compressor on the boat, down to a domestic rubber hot water bottle which acts as a pressure adjuster and so to the man’s mouth. Sometimes it happens that a diver suddenly feels himself losing consciousness because the engine fumes have been drawn into the compressor…

Nevertheless, large quantities of perlemoen were harvested and McFarlane’s factory exported the equivalent of 650 000 individual perlemoen a year. When we look at the catches of individuals the figures are also stunning. Eugene le Roux recalls:

Dave Elliot hired a small boat in Gansbaai and in one day collected 6 336 abalone in Morning’s Bay, near Buffelsjacht. George Bell claimed that he had collected 6 167 abalone in a single day. Peter Mason claimed that he collected 6 000 abalone in a day, from the boat Gemini. He asserted that the abalone were so numerous that they were one on top of another.

There are very many more stories about the perlemoen boom. However, it came to its end for the predictable reason: over-harvesting. Perlemoen numbers dropped to nothing and everyone had to get another job. Fifty years later, wild perlemoen are still scarce and those that can be found are subject to massive poaching.

It seems unlikely that ‘wild abalone’ will ever increase in numbers to the point that they can be commercially harvested and exported as in the past. Instead, as has happened to other food sources over the ages, the abalone has been ‘domesticated’, raised from sperm and eggs to marketable size and then canned and exported. Markets in the Far East seem virtually insatiable and four enterprises at the New Harbour are expanding capacity virtually all the time.

Aquaculture of perlemoen is now by far the largest activity at Hermanus’s New Harbour and the only link with divers of the past is the very cold seawater pumped through the tanks. Interested members of the public can learn first-hand about the system developed in Hermanus to generate revenue and create employment by farming and exporting abalone.

The life cycle of the abalone is fascinating and as they are held in open tanks visitors are able to see clearly each phase of the cycle. Fresh seawater is essential and one company – Abagold – pumps many millions of litres a day through the system, most of which is returned to the ocean.

‘Heart of Abalone’ provides two tours of 60 – 90 minutes duration every day. To book a tour, contact Cilene Bekker on 083 556 3428 or visit www.heartofabalone.co.za

The author wishes to commemorate Nicolas Dekker, who died last week on 15 May at the age of 87 years. He was an author and abalone diver par excellence, who assisted materially in the research for these articles.