Hermanus History Society Nomination for a Cultural Affairs Award 2016/17. Western Cape Government

May 2, 2017

Overstrand gets three secret radar stations

May 17, 2017PART 1: Radar in World War II Hangklip, Betty’s Bay and Kleinmond

Historians love to play the game of “What really won the war?” and for World War II answers range from the Secret Service hoax of ‘the man who never was’; to the decoding of German military messages by Alan Turing and colleagues at Bletchley Park; to Robert Oppenheimer and the Manhattan Project developing the atomic bomb.

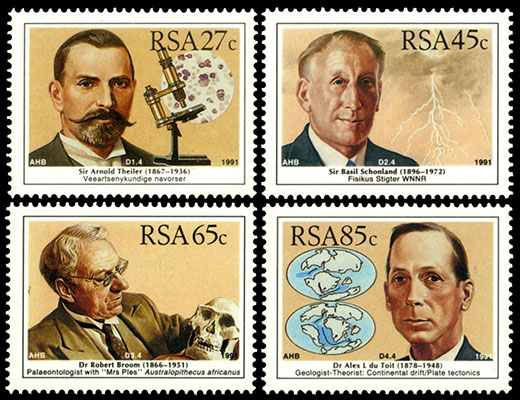

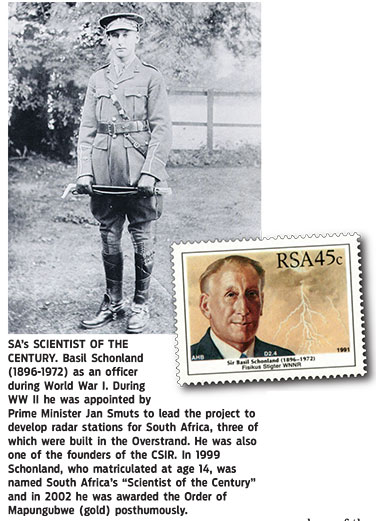

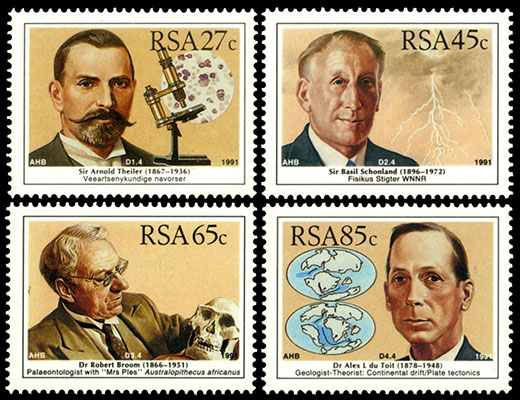

But there is a case to be made that radar was really the technology that won the war for the Allies At the beginning of World War II British anti-aircraft guns struggled to bring down even one  aircraft each day from the waves of German bombers pounding their cities. In 1940 it was calculated that the gunners, using conventional metal sights on their guns, had such difficulty in hitting their targets that, on average, 75 000 shells were fired to bring down a single enemy bomber. However, by 1943, aided by a new technology, gunners were expending an average of only 2 000 shells per plane downed. By 1945 this number had dropped into the hundreds. The new technology was RAdio Detection and Ranging, known to everyone as RADAR. It was also very effective in detecting ships and submarines (near or on the surface). Radar had a specific connection with a part of what is now the Overstrand Local Municipality. Between 1942 and 1945 three ‘radar stations’ were built in the western part of the Overstrand, one on Cape Hangklip itself, one in Betty’s Bay and a third at Sandown Bay, now Kleinmond. Several prominent South Africans feature in the story of radar in this country. The most visible was General Jan Christiaan Smuts, who, on 4 September 1939, defeated the National Party of Barry Hertzog by the vote in Parliament that took South Africa into World War II on the side of the Allies. Almost immediately, the British Government invited South Africa to send a representative – preferably a physicist – to London to be informed about a secret weapon being developed. By the end of September Smuts had selected Dr Basil Schonland, then the Director of the Bernard Price Institute for Geophysical Research at Wits University. However, Schonland never went to London, but acquired the knowledge in another way.

aircraft each day from the waves of German bombers pounding their cities. In 1940 it was calculated that the gunners, using conventional metal sights on their guns, had such difficulty in hitting their targets that, on average, 75 000 shells were fired to bring down a single enemy bomber. However, by 1943, aided by a new technology, gunners were expending an average of only 2 000 shells per plane downed. By 1945 this number had dropped into the hundreds. The new technology was RAdio Detection and Ranging, known to everyone as RADAR. It was also very effective in detecting ships and submarines (near or on the surface). Radar had a specific connection with a part of what is now the Overstrand Local Municipality. Between 1942 and 1945 three ‘radar stations’ were built in the western part of the Overstrand, one on Cape Hangklip itself, one in Betty’s Bay and a third at Sandown Bay, now Kleinmond. Several prominent South Africans feature in the story of radar in this country. The most visible was General Jan Christiaan Smuts, who, on 4 September 1939, defeated the National Party of Barry Hertzog by the vote in Parliament that took South Africa into World War II on the side of the Allies. Almost immediately, the British Government invited South Africa to send a representative – preferably a physicist – to London to be informed about a secret weapon being developed. By the end of September Smuts had selected Dr Basil Schonland, then the Director of the Bernard Price Institute for Geophysical Research at Wits University. However, Schonland never went to London, but acquired the knowledge in another way.

Sir Basil, as he later became, was born in Grahamstown in 1896, matriculated at the age of fourteen and studied physics at Rhodes University. At the age of 18 he volunteered to serve in World War I and made a distinguished contribution in the Signals Corps, for which he was awarded an OBE. After working at the famous Cavendish Laboratories at Cambridge University, he returned to South Africa at the request of Smuts and joined the faculty at UCT, soon becoming Professor of Physics. His speciality was electrical discharges of lightning strikes and in 1937 he moved to the Transvaal to head up the Bernard Price Institute for Geophysics. Obviously the Highveld provided many more opportunities to observe lightning strikes than Cape Town. He joined the army again in 1939 and, with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, started the South African Special Signals Services, which he commanded until 1941. The Special Signals Services was seen as a top secret unit in the War effort. Such was the level of secrecy that, in May 1940, when it was deemed fit to test the early radar sets over water, the unit was sent to Durban. However the officer in charge could not tell even the second in command what the convoy of trucks contained and where it was going. Everyone assigned to the SSS was administered an oath of secrecy. Because, perhaps, of the aura of secrecy created around it, the SSS was frequently given derogatory names. In the regular army the SSS was frequently called “Secret Solemn Society” or “Soldate Sonder Sense”, while the strategy of appointing only university educated women as radar operators earned the SSS the nickname “Super Snob Squad”. Geoffrey Mangin and Sheilah Lloyd, who both served in the SSS, in a paper written in 1975, describe the objectives of the unit:

With the Suez Canal closed (the Cape) was a very busy strategic shipping route – as the enemy was well aware! The object of the radar coverage was the detection and tracking of all aircraft, ships, small surface craft and surfaced submarines. This also facilitated another useful service: warning friendly shipping against running aground in poor weather and at night, with no lighthouses functioning and an enforced ‘wireless silence’. Especially ships unfamiliar with the coast and with inadequate charts. It is said that at least one ship was ‘navigating’ with a school atlas!

Schonland did not go to London for the initial briefing on radar. Instead, it was arranged that Sir Ernest Marsden, who had represented New Zealand at the talks, would meet with Schonland on board the ship on which he was returning home when it docked in Cape Town. Marsden and Schonland, two of the most intelligent men of their time, would travel together to Durban and the briefing would take place during the trip. This hastily concocted plan actually worked. While the exchange of information was taking place, Schonland observed Marsden consulting a manual from time to time, so asked if he could borrow it to study. He then went ashore and had the manual copied onto glass plates that could be duplicated by a friend at the University of Natal in Durban.

Schonland did not go to London for the initial briefing on radar. Instead, it was arranged that Sir Ernest Marsden, who had represented New Zealand at the talks, would meet with Schonland on board the ship on which he was returning home when it docked in Cape Town. Marsden and Schonland, two of the most intelligent men of their time, would travel together to Durban and the briefing would take place during the trip. This hastily concocted plan actually worked. While the exchange of information was taking place, Schonland observed Marsden consulting a manual from time to time, so asked if he could borrow it to study. He then went ashore and had the manual copied onto glass plates that could be duplicated by a friend at the University of Natal in Durban.

One of the SSS team, Captain G R “Boz” Bozzoli was a senior lecturer in Electrical Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand before the War, and later became Vice Chancellor of that University. He later described this material as ‘virtually unreadable documents (that) were the only technical papers available.’ With this resource the South African team produced its own operational radar within three months. Parts were bought from amateur radio parts suppliers and, if not available, manufactured by members of the team. The first successful trial of South African radar took place from the Wits campus on 16 December 1939, when an echo was returned from the Northcliff Water Tower, 8 km away. Later in December the range was extended to the Magaliesberg Mountains, 100 km away, and, early in 1940, an aircraft was detected in flight. During the first run of this test, the aircraft disappeared ‘off the radar’ for a short time.

This turned out not a failure of the radar. For reasons of secrecy the pilot could not be told what the mission was and he deviated from the prescribed course in order to wave to his girlfriend in her garden in Roodepoort. After a stint in East Africa to support South African and British troops, the attention focussed on the use of radar to detect naval movements around the South African coast. The first step was to establish a radar station in Cape Town

Hermanus History Dr Robin Lee