Hermanus society and the founding of NGOs: 1920 – 2020

June 9, 2020

The legacy of segregation in Hermanus

June 18, 2020As we saw in the previous article, Hermanus society and the founding of NGOs, our town has an abundance of voluntary organisations that work towards the benefit of the community and the environment. Focusing on the conservation of our floral kingdom, the Hermanus Botanical Society took root only after several false starts. But it did adapt and survive by making the changes required of it in the world in which it had to operate, writes DR ROBIN LEE of the Hermanus History Society.

T he ways in which the Hermanus Botanical Society adapted over the past 60 years are clearly documented in the publication, A Brief History of the Hermanus Botanical Society: 1960 to 2020, to which I have had access before its publication.

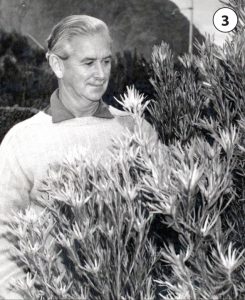

The adaptation had three components. First, leading figures in the Horticultural and Wildflower Society, notably Dr Ion Williams, became aware of global changes in the approach to nature conservation. Later, Williams wrote: We thought we were going to turn Fernkloof into a lovely garden. We knew nothing about conservation.

His intellectual influence redirected the ‘Hermanus Botanical Society’, as it came to be called. The emphasis shifted from horticulture to acting as ‘stewards’ of the natural fynbos, identifying a large number of species, removing alien vegetation and publicising the value of the Reserve to residents and visitors.

The second component of change affected the Society as a functioning organisation. Men such as Prillewitz, Williams, and Eric Jones had had experience in managing projects, and they created the programme of regular meetings, guest speakers and publicity that kept the loyalty of members going and created a sense of belonging to an initiative that was doing something important.

The third component of change was created by Williams (again) and Eric Jones. The Society needed physical projects to channel enthusiasm, and to provide an opportunity for members to contribute physical work, and strengthen the sense of purpose. Williams set about making paths in the Reserve and eradicating aliens. Jones had the brilliant idea of creating a ‘cliff path’ from the New Harbour to Grotto Beach, and generated enthusiasm by beginning work on it at once.

The Municipality supported both start-up projects and set a pattern for cooperation between the elected authority and voluntary bodies that was to have a positive impact on Hermanus history. Two themes emerged in the history of Hermanus in the second half of the 20th century and first two decades of the 21st century. They shaped the developmental path of the town and brought to light the vital role of voluntarism in Hermanus life.

The first theme was acceptance of the natural environment as a component of the town’s tourism strategy. This development was not limited to the fynbos. In time, a bird club emerged, various marine conservation projects started, and, in the 21st century, the Cliff Path itself became part of the tourist infrastructure on which public and private efforts focused.

The second theme was less favourable. Since the 1980s, successive municipalities had followed the path of consolidating their control over public contributions to conservation. Private initiatives were limited by regulations, and land usage became a source of conflict. This trend has strengthened since the establishment of the Overstrand Local Municipality.

In previous articles, I related the hesitant acceptance that Hermanus’s natural environment was at the core of its economy. By 1950, fishing as an income-generating activity and tourist attraction was failing, and along with it, the tourist-driven pastime of angling. No voluntary organisation appeared, to develop the opportunities created by the New Harbour. And no one had seen a way to support and make attractive other aspects of the natural environment.

The opportunities created by the return of the whales and the popularity of shark-cage diving were still two decades in the future. Limited numbers of visitors could enjoy tennis at the Bayview, golf at The Marine or ‘bathing’ on the beaches below the Birkenhead, but were these options any different to those available in Camps Bay or Muizenberg? Where was the attraction that would mark Hermanus as a diverse holiday destination, within the financial reach of middle-class tourists?

International trends, as well as local efforts, brought the answer: ecology and conservation of the natural environment. In 1962, Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring started the world-wide concern that human beings were destroying the natural world of which they were a part, and so harming themselves. Starting from pesticides, the fear escalated to pollution of all kinds, species-loss, and negative consequences for human health.

At the same time, other research was revealing the true uniqueness of fynbos. Fernkloof was a small area internationally but had an extraordinary diversity of species. And when its counterintuitive relationship with fire was revealed, international researchers, interested lay people and, eventually, the ordinary tourist wanted to come and see for themselves.

From 1960 the Hermanus Botanical Society was at the heart of these issues. Leading members such as Dr Ion Williams ensured that the Society kept abreast of research – and, indeed contributed to the latest work, as seen in Williams’ doctorate. Members educated themselves, as well as working strenuously in clearing aliens, creating paths and keeping records.

Mainly under Eric Jones, equally crucial public awareness was promoted. Tourists and residents of the town could enjoy the Cliff Path and the trails in Fernkloof Nature Reserve. Popular events like the annual Flower Show (later Festival) expanded awareness and generated income.

Yet, Fernkloof was legally a ‘municipal reserve’, with the Municipality designated as the manager. At the start, relations between the Botanical Society and various municipalities and other local elected bodies were excellent, and the Botanical Society was supportive and helpful. The Municipality assisted with several additions to the area of the Fernkloof Nature Reserve and permitted the Society to take the lead in some initiatives.

An example of this was the road leading to the view site on Rotary Way. A small group of private individuals saw the opportunity for access to the best view site in Hermanus. The relevant authority was quick to respond: The Caledon Divisional Council got to work, and within ten days a gravel road was completed from the Hermanus Main Road to the present parking space near the electricity pylon.

However, from the late 1990s, Hermanus began to grow, with large-scale in-migration from the Eastern Cape, and demands on the new Overstrand Local Municipality escalated. Land was desperately needed for housing and modern facilities such as hospitals and schools. Officials were told to increase income for these purposes and to scale back on support for voluntary bodies. The Botanical Society and other voluntary organisations now found themselves in an adversarial relationship with the elected authority. Publicity around the clashes heightened tension. A Brief History comments thus: The Hermanus Botanical Society has had a close association with the Reserve since the Society was founded. However, its influence has been restricted to representation on the Fernkloof Advisory Board, a statutory body appointed in terms of the Western Cape Nature Conservation Ordinance of 1974 to advise the Municipality on the management of the Nature Reserve.

Recognising the increasingly stretched responsibilities and diminishing resources the Municipality can devote to the Reserve, the HBS signed an agreement with them in 2018. The Society undertakes to maintain specific walking paths and has the authority to remove alien plants within the Reserve.

The Municipality accepted other guidelines for its action that respected what the Botanical Society had done and could do in the future. However, differences between the Municipality and the Society became adversarial in 2020, when the Society was given notice to vacate premises it had built with Municipal approval and its own funds. The Executive Mayor had to intervene to prevent legal action, but the precarious situation has remained through more than two months of the lockdown.

In one crucial area, the tolerance and mutual respect needed to sustain voluntary contributions to the development of the town has ceased to function.