Members Meeting: Monday 27 January 2020

February 10, 2020

Angling and the birth of tourism in Hermanus (1900–1970)

March 5, 2020The history of Hermanus as a fishing village 1855-1960

Writer: Dr Robin Lee

F or the first 100 years of its life, Hermanus was a fishing village. True, fishing became industrialised, and the village became a town. But, in the popular mind, fishing was the ethos of the settlement, and that sense has not changed, even in 2020. The Old Harbour, now a national monument, still lies at the heart of the town’s appeal.

The first European families that settled here in 1855, already knew about the almost unbelievable abundance of fish in Walker Bay. They had seen it, from their time at Herries Bay (Hawston). But they were pleasantly surprised to find a better inlet in the coast, protected to a degree by a promontory (we call it Gearing’s Point), though this also caused freak waves and deceptive currents.

They called the inlet ‘Die Visbaai’, not naming it after anyone and merely referring to the use they were making of it. For the next couple of decades, everyone called it by that name, whether speaking English or Dutch. But, by the early 20th century, English speakers, especially visitors, started to call it the ‘harbour’. Its present name of ‘Old Harbour’ dates from the 1950s, when the government built a ‘New Harbour’ at Still Bay, just along the coast.

Early fishing was organised on a family basis. Individual fishing boats were operated by a ‘skipper’ and a crew of seven or more men, probably all related to or close friends of the skipper. He was responsible for discipline on board, as well as seeing that each fisherman’s catch was allocated to him. The catch was mainly used to feed the families of the settlers, while some of an exceptionally good catch was salted or air-dried for later meals for the family or for sale to farmers in the area.

Nicknames were much in use by fishermen, partly because many men had the same surname. Some of the nicknames that have been recorded are John ‘Sly Fox’ Aproskie, Danie ‘Kasterolie’ du Toit, Jurie ‘Floukoffi e’ Swart, and Hennie ‘Pylstert’ Wessels.

A brochure issued by the Old Harbour Museum describes the life of a fisherman:

The return of the fishing boats to the rocky inlet was the event of the day. The boats often had to ride outside the harbour in heavy seas, waiting for a break between swells before they could row in to land their frail craft.

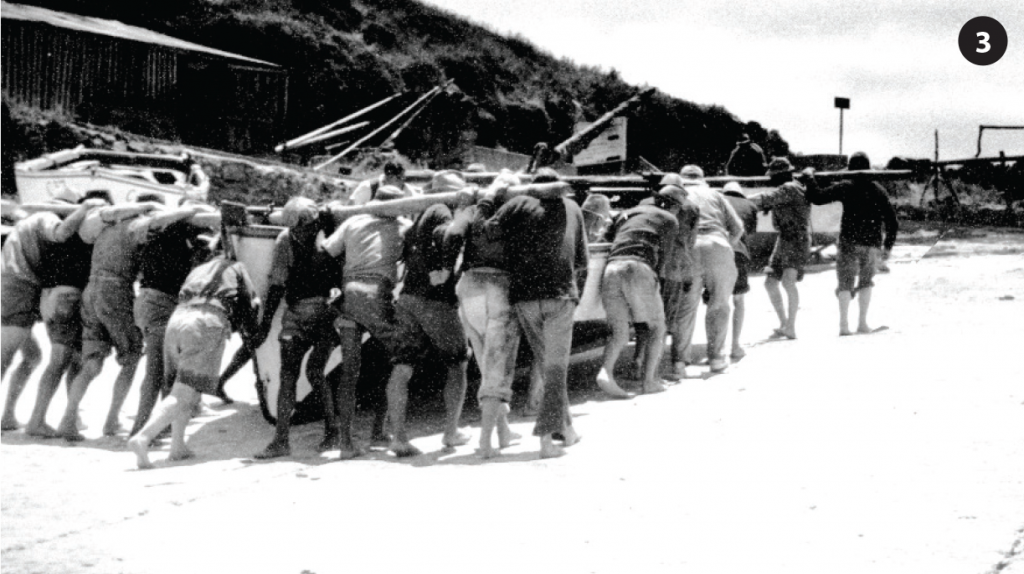

Large crowds gathered to watch this fascinating daily ritual as the catches were carried ashore and gutted and sold on the spot, while the boats were lifted and placed on the turning-stone before being carried up the slipway by sixteen men – eight fore and eight aft – straining under the carrying-poles. Some of the fish was salted and dispatched in crates for sale in other towns, while snoek and harders were salted and dried on ‘bokkom’ stands in the harbour area and in the backyards of the fishermen.

The same source describes the boats used:

At first, the boats depended on sails and oars, but later some were equipped with inboard engines. An examination of the back of the keel, through which the shaft for the screw passed, shows whether the boat was converted for use with a marine engine. However, all the boats kept a cut-out section for the mast in the second thwart. Slats from the thwart to the floor of the boat kept each fisherman’s catch separate. All the boats showed the marks of successful fishing lines under strain, gouged into the wood.

‘Subsistence fishing’ is a phrase still widely used to describe the way of life of the families at Hermanuspietersfontein, though the term ‘artisanal fishing’ is politically more acceptable.

The term ‘subsistence’ means that the activity of fishing was undertaken to feed the fishermen and their (extended) families. Fish were sold when there was a good catch. Still, sometimes there were so many fish that a surplus remained. This had to be buried soon before the stench permeated the entire village.

In Hermanus, there was always a chance of selling exceptionally large and healthy whole fish to one of the thirteen hotels that existed in the 1930s, as a special treat for their guests that very evening.

‘Artisanal fishing’ did not last much beyond the first decade of the 1900s. As early as 1885, ‘fish merchants’ set up business in the harbour. The earliest were Walter McFarlane, Adel and David Allengensky, and Eli Melnick.

They regarded fishing as a profit-making opportunity and began to re-organise the activities into a more efficient operation. First, the merchant negotiated with the skippers of boats a price at which he would buy the entire catch. The skipper then had a degree of certainty that he would realise the value of his catch and no longer depended on buyers turning up – or not – at the harbour.

The merchant then employed the same women who had cleaned fish for their families to process the catch according to his instructions and paid them a wage. The financial stability of two sources of income was a significant advance for the fisher families. The fish merchant then took steps to increase the market for the fish, fresh or processed. Quite soon, the market expanded to Cape Town and surrounds, and a Mr Joffe was credited as being the first to use ice to keep fish fresh during the journey to distant markets. There are reports of fish being exported to Mauritius, but I have not verified this.

In short, the fishing activities became part of a capitalist economy in Hermanus. This fact had a significant impact on the general economic development of the town.

Several of the fishermen were among the first to buy plots when land was put on the market after 1875. Some of them moved away from fishing and set up small businesses. An early example of this trend was a fisherman known as Jean-Louis or ‘Swede’, with the surname Wessels. He set up a boat-building and repair business in a cottage where the Burgundy Restaurant is today and supported his family as an artisan and businessman for many years.

The artisanal fishing in Visbaai existed on the cusp of significant changes in South Africa. Cities, towns and the country as a whole was moving out of the pre-industrial era and into the early stages of industrialisation. As the Hermanus economy did not include mining, manufacturing or, even, large-scale agriculture, this historical development had to occur in its underlying fishing economy.

However, it is interesting that this change that caused riots and strikes and enduring hostilities between ‘capital’ and ‘labour’ in many places, was drawn out and argumentative, but took place peacefully. Indeed, as we will see, many fisher families took to land ownership and business without much trouble.

This article forms part of an exclusive series on the chronological history of Hermanus by Dr Robin Lee. The author can be contacted on 028 312 4072 or robinlee@hermanus.co.za.

1. The Old Harbour today – a national monument that lies at the heart of the town’s appeal.

2. & 4. The Old Harbour in the early 1900s. Large crowds gathered to watch the daily ritual of catches carried ashore.

3. The boats had to be lifted and carried up the slipway by 16 men.

PHOTOS: Old Harbour Museum