Members Meeting: Monday 18 November 2019

December 17, 2019

Final Newsletter for 2019

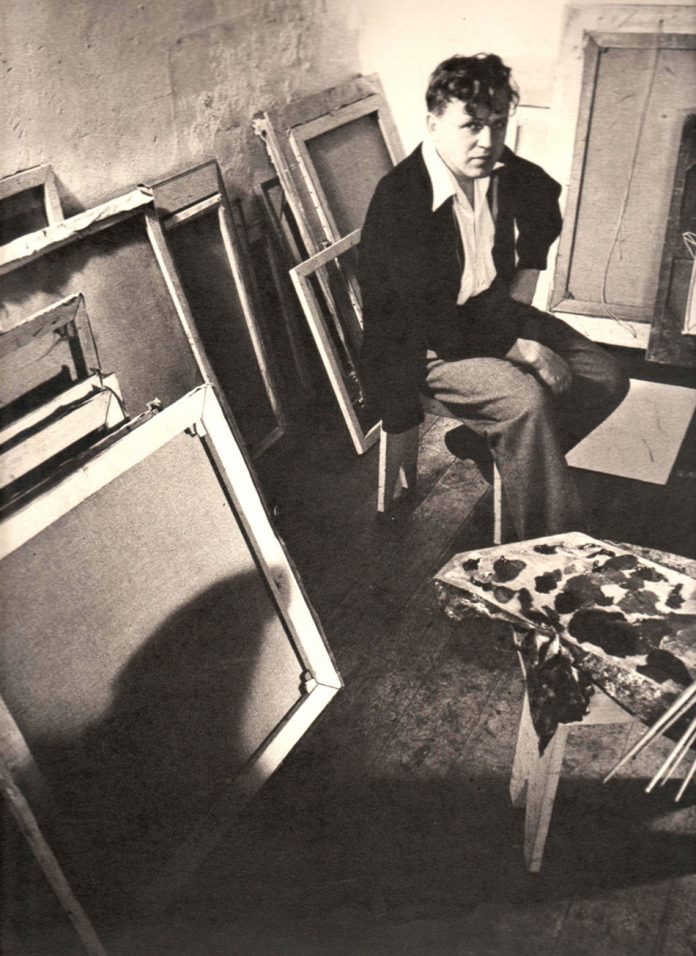

January 3, 2020Vladimir Tretchikoff (1913–2006) remains a very well-known artist of the 20th century, not accorded much value by academics and critics, but extremely popular. He is most famous for the painting Chinese Girl, which has the record of being the original painting of which the highest number of prints have been sold worldwide. The original painting itself is not doing too badly, either. It was sold in late 2013 for R17 million.

The Tretchikoff family lived in Cape Town after World War II. Tretchikoff’s wife and daughter had escaped from Singapore shortly before the Japanese captured the city and the family was separated for four years before Tretchikoff, after several narrow escapes and harrowing adventures, was able to join them.

In South Africa Tretchikoff had to earn an income any way he could and initially worked on advertising campaigns for the Schlesinger group of companies. He also worked on Anton Rupert’s first advertising campaign for Rembrandt cigarettes and was paid in shares in the company because Rupert did not have sufficient revenue to pay employees in cash.

We know that the family enjoyed holidays in Hermanus in December–January of 1950/’51, 1951/’52 and 1956/’57, staying at The Marine Hotel each time. During one of these holidays, probably in 1956, the manager of the hotel asked Tretchikoff to produce the covers of the Christmas dinner menu. Most of the guests were aware of the usual style of his paintings (such as Chinese Lady, The Dying Swan and Weeping Rose) and they were very apprehensive about what he would do with the theme of Christmas.

Tretchikoff was aware of these feelings and stunned everyone by producing delicate watercolours of fynbos vegetation. Guests kept most of the menu covers, but some have been put up for sale on the Internet. The set of four covers shown here were priced at R8 000 in 1990 and would probably sell for much more now.

Tretchikoff painted these delicate watercolours of fynbos vegetation for the covers of The Marine’s Christmas menu during one of his holidays in Hermanus in the 1950s.

Vladimir Tretchikoff was born in Russia in 1913, but was never happy there, as the Bolsheviks imposed their totalitarian rule after the Russian Revolution. He left as soon as he could with his wife, Natalie and baby daughter, Mimi. The family stayed for a short while in Harbin, a Chinese town that harboured many refugees from Communist rule. Tretchikoff did produce and sell some works there.

For safety, the family moved on to Shanghai but did not stay long. By 1940, when Tretchikoff was only 27, the family was living in Singapore where he worked as a propaganda artist for the British military. He produced many posters warning against the advancing Japanese forces and urging the populace to resist any attack on the city.

When the Japanese forces closed in on Singapore, Natalie and Mimi were evacuated from the doomed city, along with non-combatants of several nationalities. They eventually made it to Cape Town, where they waited for news about Tretchikoff.

However, back in Singapore, Vladimir’s luck had run out. As the Japanese surged into the city, he did manage to board an evacuation ship, but Japanese bombers sank it. The survivors (including the artist) took to the lifeboats and tried to escape by rowing. They reached Sumatra after two solid weeks rowing but found it already occupied by the Japanese. They could not land, so spent another 19 days rowing to reach Java.

Once again, they found that the Japanese had seized the island and were soon captured. Tretchikoff was still a Russian citizen, so he was not sent to the notorious Japanese concentration camps, but allowed to work in Jakarta on parole. He remained there for the rest of the war.

Tretchikoff was released soon after Japan surrendered in 1945, but confusion and lack of transport meant that two more years passed before he was reunited with Natalie and Mimi in Cape Town in 1947. The family decided to stay there. He became a prolific painter. In 1948, Tretchi (as he became known) had his first exhibition in the shop of the publishers Maskew Miller, in Cape Town. Queues stretched down Adderley Street.

Vladimir Tretchikoff

In 1952, he exhibited in Los Angeles (57 000 visitors attended the exhibition), San Francisco (52 000 visitors) and London (205 000 visitors). The artist participated in every minute of every show and used a hand-operated counting device to keep track of the number of visitors.

Massive public exhibitions became a Tretchikoff trademark which he repeated several times in South Africa. They attracted media attention and promoted the sales of prints. According to a recent (2013) biography by Boris Gorelik, Tretchikoff held just over 50 shows during his life, attended by an estimated 3 million people.

Very recently, the identity of the woman who was the model for Chinese Girl has become known. She was Monika Sing-Lee (later Pon-Su-san) and Tretchikoff approached her to sit for him when, as a teenager, she was working at her uncle’s launderette in Sea Point. The model for two other famous paintings has also been identified. She was Valerie Howe who was a friend of Monika’s, and she appears as Miss Wong and Lady from Orient. Valerie Howe died in 1995.

According to Tretchikoff’s biographer, prints from both these paintings have done exceptionally well. In Britain, Miss Wong became the sixth best-selling print of 1960, while Lady from Orient found its way into second place in the British top ten (prints) of 1962, the highest position for any Tretchikoff print since the country-wide poll was first conducted.

Tretchikoff broke with the artistic elite, both in subject matter and style of painting and in marketing his work. His painting style was influenced by the art deco movement and by advertising work he had seen. His marketing strategy was to avoid art galleries and instead exhibit in department stores, to reach a wider public. He also supervised the production of prints of his works, for purchase by ordinary folk. Both strategies were highly successful.

South Africa began to change politically in the 1970s, and black artists began to make themselves known. Tretchikoff found himself accused of representing men and women of colour in his paintings in a derogatory way and diminishing their status. Sales of his works and the prints based on them dropped, and his most recent biographer describes his situation at the end of the 1970s as follows:

Tretchikoff was no longer a major newsmaker, even for the local press. Cape Town papers wrote about him only when he and Natalie attended social events or when Vladimir got into petty disputes. Ons such occasion was when their Alsatian bit a neighbour, Andries Treurnicht, the Minister of Public Works, Statistics and Tourism at the time, on the leg.

However, in the 1990s, prints of his work began to appear in apartments and houses in many European cities. The provenance was quite different. Now the prints were incorporated in the décor of trendy young people, either because they remembered them on their parents’ walls or because they represented a single finger gesture towards the attitudes of the established art world.

As far as his original work is concerned, it too has survived criticism and a refusal to consider it as art. In 2010 a retrospective exhibition was held in the National Gallery in Cape Town. It turned out to be the second most popular exhibition ever held there. At the same time, prices paid for original works by Tretchikoff began a meteoric rise. It started with a work called Fruits of Bali, which fetched R3 400 000. In quick order, others fetched R1,5 million, R4,4 million and, as already mentioned, Chinese Girl a whopping R17 million. Red Jacket, a portrait of Lenka, the artist’s mistress, sold for R4,5 million in London.

Vladimir Tretchikoff died in Cape Town in 2006. It is not known whether he revisited Hermanus after the 1950s.