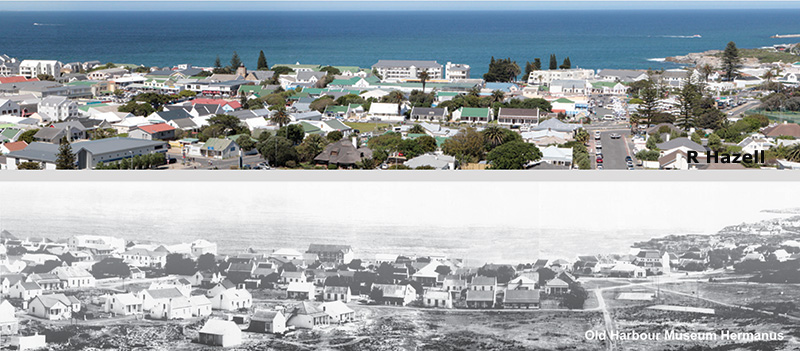

Aberdeen Street in history – 1870 to 2017

September 28, 2017

How I won the Victoria Cross – Story of Major William Hewitt

October 5, 2017Another process of research, another unlikely link uncovered between Hermanus and events of world significance a long way away. This time it is the “Burma Campaign” that took place in the country we now call Myanmar between 1942 and 1945. It started with the Japanese invasion of Burma in preparation for the final target – the invasion of India and access to natural resources to sustain the Japanese military campaigns. For the Western Allies High Command, however, the bitter fighting in Burma was seen as far less important as defeating the German forces in Europe. Indeed, the Burma Campaign has often been called “the forgotten war”.

Yangon (known in the 1940s as Rangoon) is roughly 10 000 kms from South Africa, so connections between the two countries seem unlikely, never mind a link between a serviceman in Burma and a specific small town in South Africa. But it exists in the persons of Berdine Luyt, Gertrude Grant and a previously little-known teak planter, elephant whisperer and Member of the Order of the British Empire, Major Harold Langford-Browne.

Yangon (known in the 1940s as Rangoon) is roughly 10 000 kms from South Africa, so connections between the two countries seem unlikely, never mind a link between a serviceman in Burma and a specific small town in South Africa. But it exists in the persons of Berdine Luyt, Gertrude Grant and a previously little-known teak planter, elephant whisperer and Member of the Order of the British Empire, Major Harold Langford-Browne.

Harold Browne (as he was known in Hermanus and surrounds in the 1960s) was born in Cape Town in 1907. At present, I do not have his South African family details. He attended school here, but went to Britain for his university education. After graduating he decided not to return to South Africa, but joined the major private company operating in Burma, the Bombay Burma Trading Company. One of the many activities of the company was the logging of natural teak and the development of teak plantations for future supply. Teak is a particularly hard and durable wood which was used for many specialist purposes at that time.

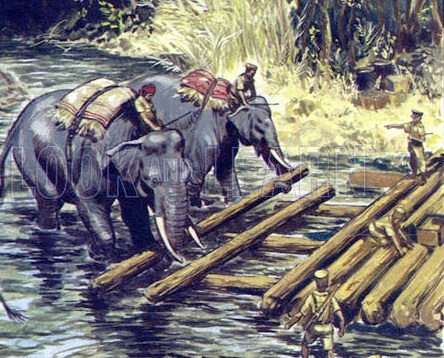

The industry of teak production still made extensive use of elephants in its work. Elephants could make their way through the densest undergrowth to the locations of natural stands of teak. They could also be trained to push over trees that had been partially cut, to lift logs with their trunks and tusks and pile them neatly and to carry equipment, supplies and personnel on their backs.

In the 1920s and early 1930s Harold Browne developed an exceptional accord with the elephants on his plantation and was soon famous throughout Burma as an ‘elephant man’. According to one biographer he ‘was handsome as a matinee idol and beloved by the uzis.’ [the local name for the elephant handlers]. But even his reputation was overshadowed by an older Company employee, later internationally famous in books and films. He was J H (Elephant Bill) Williams.

Williams believed passionately that elephants are intelligent and emotional animals which can form strong bonds with humans, develop skills and follow instructions of a much more sophisticated kind than those used by the Burmese ‘uzis’. He dreaded any elephant falling into the hands of the Japanese who mistreated them very cruelly. The best way to protect the elephants was to make them an integral part of the Allied military. So that was what he set out to do.

As a partner in this mission, Williams immediately recruited Harold Browne. He records these words in his book, “Elephant Bill”:

As a partner in this mission, Williams immediately recruited Harold Browne. He records these words in his book, “Elephant Bill”:

The first ‘hire’ was Harold Langford Browne, my old buddy, now with the Indian 23rd Infantry Division of the British Indian Army…South African by birth and a man of magnificent physique, with broad shoulders and narrow hips, Scandinavian blue eyes, and hairy all over, like a gorilla. Most important were his loyalty as a friend and his affection for the ‘uzis’. He would not tolerate any colonial posturing toward them. Harold was more loved by the Burmese than anyone I ever knew. And he knew plenty about elephants.

Together, Williams and Langford-Browne created ‘the Elephant Corps’ that over the period of the war grew to dozens of men and hundreds of elephants. Their first task was to recover elephants that had been trapped behind enemy lines. Browne spent ‘several months’ playing cat-and-mouse with the enemy in the nearby forests. He returned with 40 elephants. Then they were ordered to evacuate British women and children out of Burma and away from capture by the Japanese. This was a great success and some 250 civilians were carried by elephants to safety in India.

Williams and Browne then adapted techniques from their plantations to assist the Army. The most important was bridge building, a necessity for any movement in the tropical jungle environment. The elephants were able to lay logs next to each other in the rivers with such accuracy that they would not slip apart when under pressure. In fact, once the bridge was laid by the elephants, it was immediately available for use by soldiers and by motorised transport. The work was also carried out virtually silently and so avoided detection by the enemy, which could never have been achieved with bulldozers – and the Allied forces didn’t have any bulldozers, anyway.

Another book about Williams and Browne describes a difference of opinion about bridge-building between the conventional military engineers and the Elephant Corps:

The chief engineer had wanted a wide bridge, configured for two way traffic, but Williams told him two simple bridges, the kind elephant men and elephants were accustomed to building, would do the trick…They started work on December2, 1942, and were finished ahead of schedule, on the 15th, when a whole brigade and their trucks passed over it.

do the trick…They started work on December2, 1942, and were finished ahead of schedule, on the 15th, when a whole brigade and their trucks passed over it.

Early in 1944, Browne suffered severe back injuries when his vehicle crashed into a tree during an engagement with the Japanese. Nevertheless, by the end of the war he had had risen to the rank of Major and in 1946 he was given a higher level of recognition: Member of the British Empire (MBE).

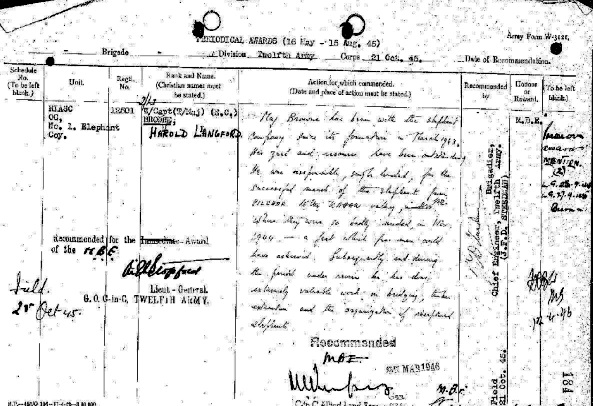

The award was gazetted in the London Gazette of April of that year. I managed to obtain an image of the actual handwritten citation, signed by Lord Louis Mountbatten, which was sent to me after I made an appeal on military websites, by a gentleman in the Netherlands. It reads as follows:

Mr. Browne has been with the elephant company since its formation in March 1943. His zeal and resource have been outstanding. He was responsible, single-handed- for the successful march of the elephants from Pyinama to the Kalewa Valley, where they were so badly needed, in November 1944 – a feat which few men could have achieved. Subsequently and during the period under review he has done extremely valuable work on bridging, timber extraction and the organisation of recaptured elephants. (21 October 1945)

In another book the work done by Williams and Browne is described as follows:

In 1944 Williams moved the elephants back into Burma, “where their work would change the course of history. In part (this was) due to the 270 bridges they built from local materials, before lightweight prefabricated sections were available to build the largest known Bailey Bridge, which was built across the Chindwin at Kalewa in December 1944.

By the end of the war Williams and Browne were managing 1652 elephants but the injuries from his accident and the pressure of working under constantly dangerous conditions had impacted Browne’s health. By 1944 the Japanese were retreating rapidly and abandoning elephants they had captured during the fighting. These needed to be rounded up and brought back to base. Williams records Browne’s role in this:

…Browne was left to bring the elephants back alone. He was quite confident that he could, and he did so successfully, but he did not really recover from the exhausting strain of being the only officer in charge of them…He then went on leave to South Africa, with his job completed, four days after the Japanese surrender. No man ever deserved leave more.

Williams does not record the duration of Browne’s leave, but he does refer to Browne returning to continue work in Burma. We may deduce that Browne spent several months in South Africa in 1945-1946 and it may have been then that he first visited Hermanus.

I am still researching Browne’s life between 1946 (when he left the army) and 1958, but we know with certainty that in 1958 he bought a portion of the farm Wesselshoek in the Gansbaai area, about 50 kms from Hermanus. The owner at the time was Stuart Cloete, the well-known South African novelist. Browne paid £6000 for 168 hectares that we now know as Grootbos, a 5-srar eco-resort. Harold lived there until 1964, when he sold the farm and moved into Hermanus. He suffered great pain from his back injury which required constant attention and he could not continue alone on the farm.

At this point in my research, it became clear that there was a link between Harold Browne and people in Hermanus. In the years 1970 to 1972 Berdine Luyt, the eldest daughter of Joey and John Luyt, owners of the Marine and Riviera Hotels, wrote many letters to a man she identifies as “Harold Browne”. I had found them amongst her papers (generously made available by the Luyt family) and initially could not place them at all and had no idea who this person ‘Harold Browne’ could be. Now I realised that there was a person of that name alive, but not well and living in Hermanus at the time.

From about 1965 to 1971 Harold Browne lived in an apartment in Marine Court, which occupies a site fronting Walker Bay, near the Old Harbour, and with an entrance in Main Road. The building still exists. In Browne’s time it was adjacent to Hamewith, the home of Sandy and Gertrude Grant. Sandy Grant was the first pharmacist in Hermanus and Gertrude was well-known for her care of wounded soldiers in World War II, though these events were long after the war. Gertrude would have welcomed an opportunity to help and care for another wounded soldier.

In turn, Berdine Luyt was close to the Grant family and would thus come to know Harold, who probably did not get out much due to his poor health, and to write him letters. The links in

the chain were complete. According to a final letter from her to him, it appears that he had decided to return to live with a sister in the UK.

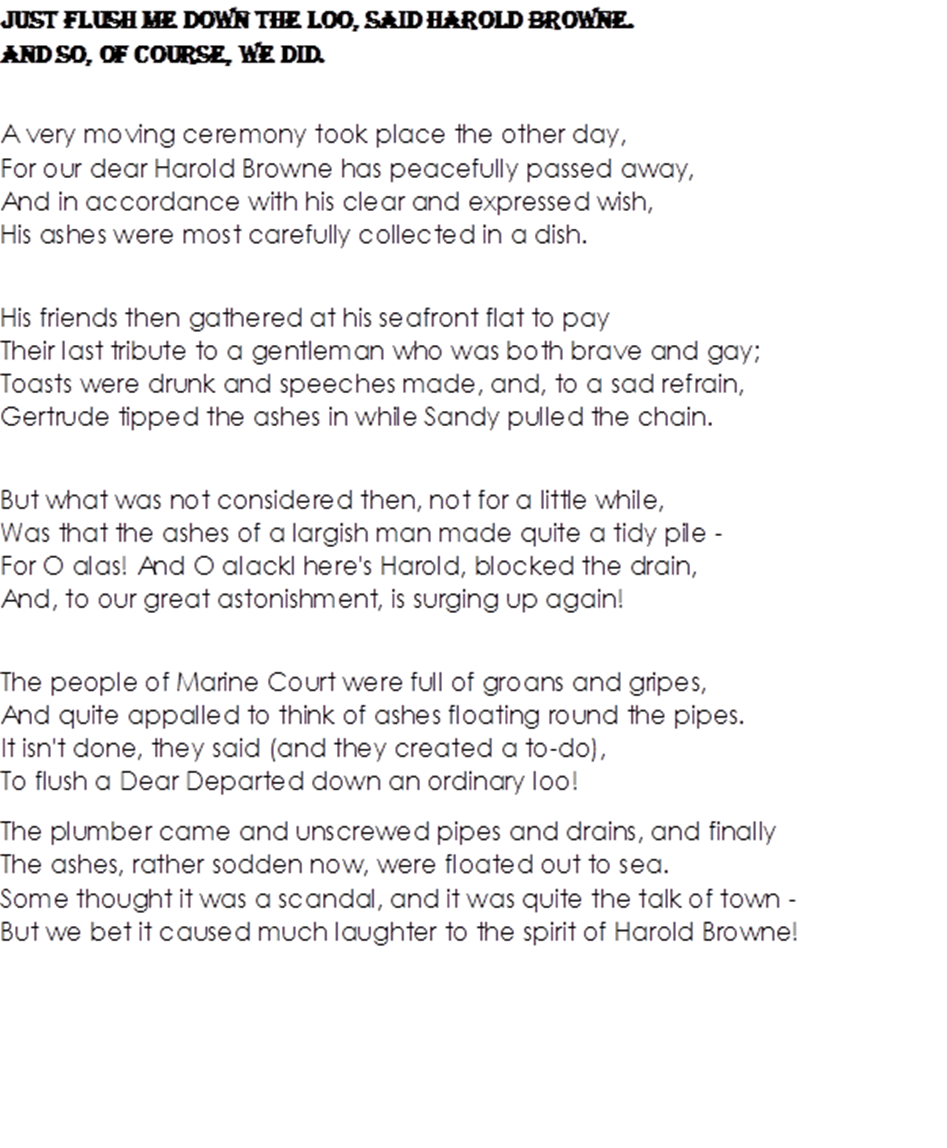

However, behind that letter, partly hidden is the poem that follows. My experience of the truthfulness of all the rest of Berdine’s writings, leads me to think that maybe Harold Langford-Browne passed away through the sewage services in Hermanus.

However, behind that letter, partly hidden is the poem that follows. My experience of the truthfulness of all the rest of Berdine’s writings, leads me to think that maybe Harold Langford-Browne passed away through the sewage services in Hermanus.