WHO WAS WALKER OF ‘WALKER BAY’?

January 30, 2017The Marine was Hermanus’ very own Fawlty Towers

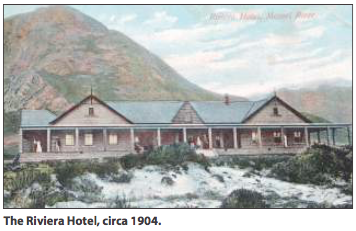

January 31, 2017Grotto seems to have been named after the caverns set in the rock face behind Dutchies restaurant. The earliest written reference I have found to these “Grottos” is in a Memoir by Nancy Okes (neé Napier) whose family travelled from Cape Town every year in the 1920s and 1930s to holiday in Hermanus. The family always stayed at the Riviera Hotel, which was quite near the Grottos and approximately where the Sandals residential development in 11th Street, Voëlklip, is today.

Nancy uses the term ‘Grottos’ as if everyone knew what and where they were and does not mention any other name by which they might have been known. However, it appears as if the area was known as the Varingkloof before it was anglicised to Fern Kloof, and later still it was simply referred to as the Grottos. According to Nancy, children found the Grottos irresistible:

“The Grottos lay to the west of the Riviera Hotel, across the mashie golf course. The ground fell away sharply into a donga. The mountain stream at the Riviera entrance flowed down to service the Grottos, running round the top and tinkling down the rock faces all the way round. The Grottos themselves, five or six large caverns, lay in the rock face, in a semi-circle. To reach them, one had to clamber down the rocks.”

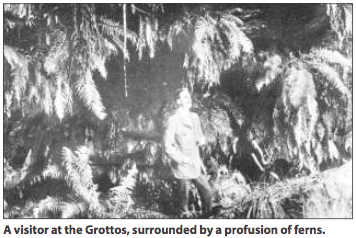

In the photograph on the right, which seems to have been taken in the 1920s (judging from the man’s clothing), the profusion of ferns is clearly illustrated. The photograph is captioned “The Fern Kloof, Now the Grotto” and is one of only two photographs I have been able to find of the Grottos in their natural state. Nancy’s description continues:

“The Grottos faced onto a small vlei in which grew tall blue Aristea and golden Wachendorfia and reeds, about 5 feet high. In amongst their tall blooms rioted the weaver birds, finches as gold as guineas, scarlet Bishop birds and the black and red Widow birds. The males, in full mating garb, were building their nests while the females perched, apparently disinterested, nearby.

“Each grotto had a rocky floor with pools and frogs and tadpoles. The walls were festooned with maiden hair fern and on their ceilings slept the bats, black and upside- down. Around the circum- ference of the vlei ran a mossy path, enabling us to flit from cave to cave, enchanted. The Grottos were pure magic with moss, ferns and water dripping down. All this ended when the water was cut off when they built the new road.”

The ‘small vlei’ to which Nancy Okes refers, we would now call a wetland. Most residents at the time referred to it as a ‘swamp’. It occupied virtually all the space between the first of the dunes, where the road to Dutchies restaurant and the beach runs now, and the Grottos themselves. Frank Woodvine, former curator of Fernkloof Nature Reserve has told me that the famous Dr Ion Williams, who created the reserve, spoke often about the wetland. Specifically, he mentioned that when he was a boy there was enough water for him to paddle his canoe around the wetland and that wild geese visited the wetland as a migratory stop-over point each year.

As more houses were built at the top of the cliffs containing the Grottos, the streams Nancy refers to ceased to be clear and became polluted in various ways. In turn this introduced pollution into the wetland.

Long-time Hermanus resident Michael Clark recalls the changes as seen from a family perspective:

“When our children were small – late sixties and possibly the early seventies – there was a pipe under the road more or less where the present parking area is, just past the restaurant and changing rooms. This was a pipe of about fifty millimetres and was supposed to drain off the excess water from the vlei. For a short distance the water flowing out of the pipe formed a small river on the beach and then disappeared into the sand. It was a wonderful place for young boys to play, building dams.

“My wife Pat and I would take our sons there often to play. One day Dr Cohn [well-known Hermanus doctor who shared rooms in Harbour Road with Dr. Daneel] walked passed and said the water was polluted and that it was not a good idea for the children to play there. Pat, who was an ex- nurse, was incensed and thought Dr Cohn was over- reacting.

“Next day she went to the Municipality and asked them to have the water tested. Lo and behold, the water had a huge pollution count. This was caused by the septic tanks and soak-aways on the properties above the Grottos. There was no sewage system in Voëlklip in those days.”

The pollution made it essential for the municipality to intervene, but what followed was probably an over-reaction. In December 1968, the Birkenhead Hotel, one of Hermanus’s best- known and popular hotels, was damaged by fire. According to some accounts, it was decided to use ‘spill’ (rubble) from the demolition and rebuilding of the damaged sections of the hotel to completely fill the wetland. Soil was put on top and grass grown. The stabilised area was then opened to the public as a picnic area. However, I have been unable to confirm this sequence of events.

Despite health issues, the wetland had provided a natural barrier between the Grottos and the holiday public. Removing this barrier brought holiday crowds right up to the entrances to the Grottos and quite soon the clear pools mentioned by Nancy Okes became polluted with empty beer cans, bottles of all sorts, paper, cigarette butts and the like. Little attention was given to the preservation of the luxuriant ferns and other plant life and at the time that this article is written, the Grottos are an eyesore rather than an attraction to tourists.

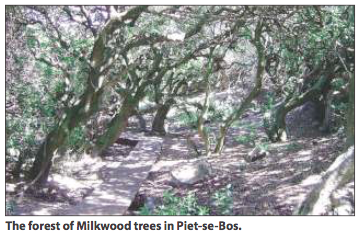

Adjacent to the Grottos and the wetland is a stand of milkwood trees, possibly the largest stand in Hermanus today. It is known to Afrikaans and English speakers as “Piet-se-Bos”, but there is no information as to who Piet was. Yet the short walk through Piet-se-Bos gives some idea of the beauty of the coastline before people came and built houses. Under the milkwood trees it is cool and shady and any walker passes silently on the soft surface of fallen milkwood leaves and sea sand. A stream runs through the wood and there is a small pool, with ferns growing all around. To prevent damage to young milkwoods, a wooden boardwalk has been built through most of the area.

With commendable foresight the whole of Piet-se-Bos has been declared part of the Fernkloof Nature Reserve and two voluntary bodies, the Cliff Path Management Group and Whale Coast Conservation, keep it as pristine as possible. Meanwhile, intense discussion has been taking place between the Municipality and the ‘interested and affected parties’ as to the best way to bring the components - the Grottos, the existing restaurant, the old wetland and Piet-se-Bos - into proper use. As yet, there appears to be no resolution.

Dr Robin Lee of the Hermanus History Society can be contacted on 028 312 4072 or robinlee@hermanus.co.za